By Dorothy Hoard

Spring 2010

Like many other creatures of the earth, butterfly populations are showing signs of stress. In many places in North America, once-common butterflies are no longer common. Some are now being nominated for threatened or endangered status. Advocacy groups are mounting campaigns to create microhabitats suitable for specific kinds of butterflies or provide for sanctuaries for a wide variety of butterflies.

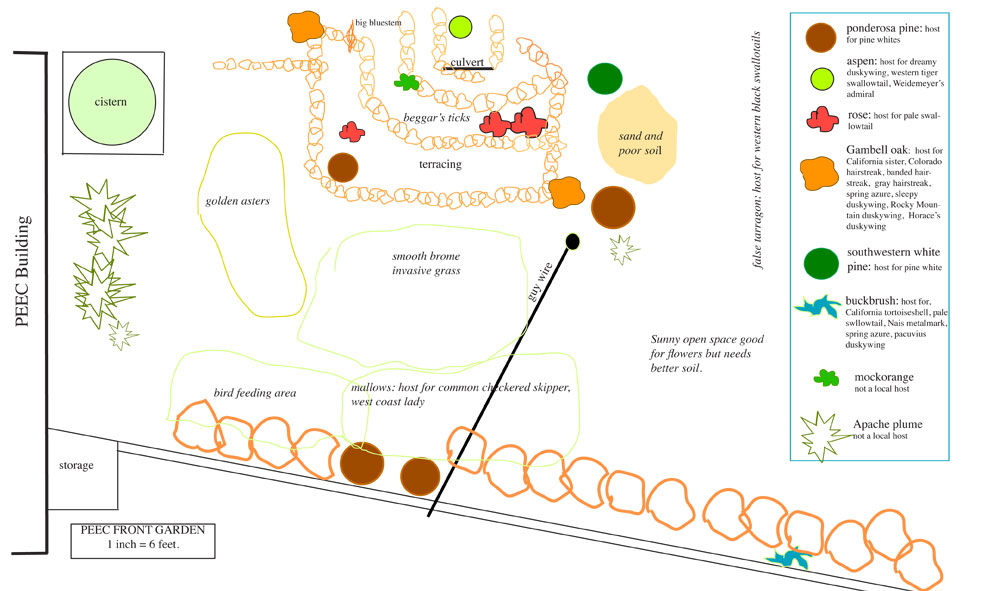

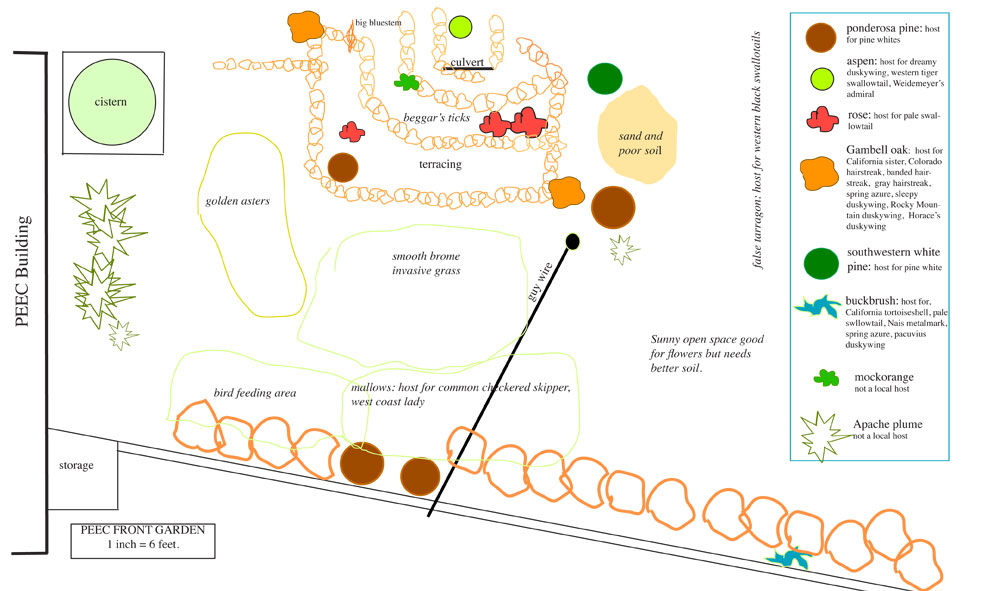

The North American Butterfly Association (NABA) has set up a certification program to encourage individuals or groups to create gardens as safe havens with types of plants that butterflies and skippers need for survival. The Pajarito Environmental Education Center (PEEC) has a Wildlife Habitat Garden certified by the National Wildlife Federation that can easily be expanded to do double duty.

Most butterflies need two kinds of plants Ð so-called host plants and nectar plants. A host plant is one on which a female lays her eggs; its leaves provide food for the caterpillars. While a few butterflies (and many skippers) are generalists--the caterpillars can survive on a number of plant species--many butterflies have very specific host plants.

The well-known monarch butterfly is dependent on milkweeds of the genus Asclepius to make its famous long-distance migrations from the mountains of Mexico to the meadows of Canada. An individual monarch cannot make the entire journey north on its own; the species must find milkweeds along the way to lay eggs for the next generation to continue the trip. Conservationists are concerned that continuing habitat destruction will disrupt future migrations by eliminating milkweed patches. On the other hand, the caterpillars of our other famous migrant, painted ladies, (the butterflies released at weddings) can survive on a wide variety of plant species.

PEEC already has a number of butterfly host plants in the garden or in the surrounding Olive Street Canyon area.

The other type of plant part that most butterflies require are nectar flowers. These plants usually have numerous, brightly-colored, small flowers. Many plants of the sunflower family make excellent nectar flowers; in our area, the native cut-leaf coneflower is a fine example. The all-time champion nectar plant is butterfly bush, a native of Asia. We are collecting data from local gardeners on which plants they see butterflies finding nectar.

Butterflies and skippers have other requirements as well. They require full sun to fly; the warmth allows them to pump fluid into their veins to stiffen their wings. Butterflies often bask on light-colored rocks (available at the PEEC garden), spreading their wings to absorb heat from the sun. (Moths don't have this need and can fly at night.)

We expect the PEEC butterfly garden to be an experimental one. One of the expectations of our garden watchers is to generate a list of nectar plants we can recommend as butterfly attractors for high altitude areas similar to ours. Can we find nectar plants for spring and summer, as well as autumn? Another concern is to try to determine how much shade butterflies and nectar plants can tolerate in our pine-covered environment. How does the urban environment affect butterflies? Will the adjacent large parking area be a source of warmth for them or just a deterrent? Will they use the little damp puddling area we will create for them. Can we attract more species than our usual high-flying, long distance swallowtails and ubiquitous painted ladies? How large a patch of host or nectar plants will butterflies need to find our garden and to move in?

PEEC specializes in outdoor education projects for students. The children are enthusiastic about the butterfly garden and have already made helpful suggestions.

Return to PEEC website Articles by Local Authors.

Below is the schematic diagram for the butterfly garden, drawn by Dorothy Hoard.